Issue Brief | The State of PFAS Forever Chemicals in America (2024)

By Molly Brind’Amour

September 6, 2024

The term “perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances” (PFAS) refers to a group of thousands of synthetic chemicals with specific heat-, grease-, and water-resistant characteristics. These substances are distinguished by their chemical structure, which includes a chain of fluorine-bonded carbon atoms. PFAS entered the homes of everyday Americans in the 1940s, and can be found in at least 200 different use categories and applications, including firefighting foam, food wrappers, cosmetics, clothing, cookware, and household products.

Often referred to as “forever chemicals,” PFAS possess a chemical structure that makes them extremely difficult to break down. Definitions of PFAS vary, so the exact chemicals included under the umbrella term differ from one organization to another. In addition, categories within the PFAS label, such as “long-chain” and “short-chain” PFAS, have different properties, such as shorter or longer half-lives.

Wide usage over many decades has led to the presence of PFAS in soil and water, thus leading to the contamination of fertilizer, livestock, and drinking water. Furthermore, studies have found that at least 97% of Americans tested had PFAS compounds in their body fluids. While the health effects of PFAS are still being explored, evidence suggests that forever chemicals can cause health issues, including reduced fertility, childhood development problems, and increased cancer risk. This white paper reviews the current extent of PFAS contamination, its effects on humans, the federal, state, and local landscape for regulating PFAS, and options for further remediation and mitigation.

Six Common PFAS of Concern to the EPAThe EPA has established maximum contaminant levels in drinking water for these PFAS |

|

|

PFOA |

PFOA has been one of the most commonly used PFAS in the United States, though it is no longer manufactured here. It is the most widely studied PFAS, and is classified as “carcinogenic to humans” by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). It is found in carpets, cables, cookware, and personal care products, among other things. |

|

PFOS |

PFOS is another common PFAS that is often used to make products resistant to water, stains, soil, and grease. Like PFOA, it is no longer manufactured in the United States. It is classified as “possibly carcinogenic to humans” by IARC. It was used in firefighting foam through 2001, and is still present in some stocks of this foam. |

|

GenX Chemicals Hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid and its ammonium salt |

GenX is a category of newer PFAS used as replacements for PFOA. These chemicals are used in applications like nonstick coatings and food packaging. GenX chemicals can be more mobile than older PFAS, meaning that they can cause exposure even from farther away. Research suggests that the liver may be sensitive to oral GenX exposure. |

|

PFBS |

PFBS is often used as a replacement for PFOS. Common uses include coatings on fabric, carpet, and paper. Research suggests that the thyroid may be sensitive to oral PFBS exposure. |

|

PFNA Perfluorononanoic acid |

PFNA is commonly used to make fluoropolymer coatings for products like carpets, food wrappers, and cleaning products. There are concerns for PFNA’s effects on reproductive systems and development, but more research is required. |

|

PFHxS |

PFHxS is phased out of production in the United States, though it may still be present in imported goods. It has been used in fabrics, firefighting foam, food packaging, and more. PFHxS is associated with potential liver and antibody effects. |

The Prevalence of PFAS

Forever chemicals come into contact with humans through two main pathways. The first is through the manufacture and use of products that directly contain PFAS, like certain candy wrappers, firefighting foam, floss, and pizza boxes. The second is through contaminated water and soil, and the things that grow in soil or take in water, such as livestock, fish, and produce. People can be exposed to PFAS by drinking contaminated water, inhaling chemicals in a manufacturing setting, ingesting contaminated soil or dust, eating food that has been exposed to PFAS (i.e., through soil or packaging), or using consumer products made with PFAS. Recent data even suggests that forever chemicals can be found in snow and raindrops.

Firefighting foam, commonly used at military bases, is considered a significant culprit in contamination, particularly through drinking water. Aqueous Film-Forming Foam (AFFF) made from forever chemicals became popular due to its ability to quickly extinguish fires and prevent reignition. By the 1960s, the U.S. Navy mandated that its vessels carry AFFF. In 2014, 664 U.S. military training sites were identified as likely to have PFAS contamination. However, since October 2023, a Department of Defense (DOD) interim rule prohibits DOD procurement of AFFF with more than one part per billion of PFAS, unless an exception has been made.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has identified around 120,000 U.S. facilities that may have handled or released PFAS. And as of August 2024, 2,067 sites in the United States have detectable levels of PFAS contamination in their drinking water. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that at least 45% of U.S. tap water contains PFAS. Incidences of drinking water and military site contamination have been recorded in all 50 U.S. states, but PFAS pollution isn’t distributed equally. Residents of Black and Latino communities have a higher likelihood of having dangerous concentrations of forever chemicals in their water supply compared to residents of other areas. While contaminated drinking water tends to lead to higher PFAS exposure, PFAS are also present in consumer products. PFAS are used to make so many different products, from contact lenses to varnish to guitar strings, that without further regulation it is difficult for consumers to understand which products may contain the chemicals. Manufacturers of consumer goods are not required to disclose to consumers whether a product contains PFAS, leaving consumers to rely on lists of PFAS-free products compiled by outside groups and voluntary commitments from companies to phase out these chemicals. Further complicating matters, when stain- and water-resistant products used by or marketed to children and adolescents were studied, products labeled “green” nevertheless often included PFAS.

Three PFAS were banned from food packaging in 2016, but thousands of chemicals remain unregulated. Two of the most widely used and studied PFAS—perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS)—are no longer made in the United States. But these PFAS are still present in the United States through imported products, older products, and legacy contamination from firefighting foam.

Effects on Humans

Because PFAS are so prevalent, the chemicals may be affecting humans. The health effects of PFAS can vary based on the individual chemical in question. Commonly discussed PFAS include PFOA, PFOS, GenX (a trade name for an ammonium salt used to replace PFOA), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS).

Perhaps the most troubling health concern is the linkage of PFAS to cancer. PFOA is listed as a known carcinogen, while PFOS and GenX (PFOA’s replacement) show “evidence of carcinogenic potential.” As the National Cancer Institute’s page “PFAS Exposure and Risk of Cancer,” explains, PFOA is linked to higher kidney cancer rates and mortality for those working in or living near PFAS plants. PFNA, meanwhile, has been linked to higher risk of renal cell carcinoma even in general populations, particularly among Black people. High levels of PFOS have also been associated with an increased risk of testicular cancer. Researchers are planning and implementing studies to determine the effects of PFAS on breast, ovarian, endometrial, and thyroid cancers, among others.

Cancer is not the only health condition linked to PFAS. Current research indicates that both PFOS and PFOA can suppress immune responses. Forever chemicals can also contribute to hormone disruption: research shows that short- and long-chain PFAS can have endocrine disruption effects, with stronger thyroid hormone disruption effects on women (which could affect their metabolism). Furthermore, a literature review of eight common PFAS included studies linking PFAS to health complications, such as increased levels of the thyroid-stimulating hormone thyrotropin, adult and child obesity, diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome-related infertility, chronic kidney disease, impaired lung function for asthmatic children, and deficient antibody responses. Children are particularly vulnerable to the negative effects of PFAS, given their greater exposure per pound of body weight and their continuing development.

For individuals, PFAS concentrations will vary based on exposure factors (like where people work and live) and excretion rates, which depend on biological factors, such as whether a person is breastfeeding or has kidney disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data compares PFOS, PFOA, and PFHxS blood levels in studies of the general U.S. population and groups with community and occupational exposure. PFOS and PFOA levels in blood have declined by more than 85% and 70%, respectively, since 1999 but there are concerns that Americans are being exposed to other PFAS that are not part of the study.

Blood testing can help people develop a better understanding of their PFAS levels, but it cannot determine what health effects those chemicals have caused for an individual, or how they were exposed. Further research is needed to determine how concerned people should be about their PFAS levels, as well as to analyze the effects of and treatments for exposure to the hundreds of PFAS available commercially.

Federal Regulation

The EPA’s 2021 PFAS Strategic Roadmap serves as the Biden-Harris Administration’s action plan for addressing forever chemicals. The EPA took a number of key actions toward this roadmap in 2023. It eliminated a PFAS Toxics Release Inventory exemption and finalized a rule mandating that manufacturers and importers of PFAS and PFAS products report relevant information about the uses, disposal, and hazards of the forever chemicals. Other actions include improving the evaluation of new PFAS and new uses for PFAS, allocating $2 billion in Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (P.L. 117-58) funding for the cleanup of emerging contaminants including PFAS, and requiring revised Effluent Limitations Guidelines for PFAS in landfills. EPA also released an advance notice for public input on the future inclusion of certain PFAS in the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), commonly referred to as the “Superfund Law.”

Superfund designation would impose retroactive, strict, and “joint and several” liability for cleanup and damages on parties considered responsible for PFAS contamination. “Joint and several” liability means that any “potentially responsible party” for the contamination may be held responsible for cleanup costs if it is unclear which party caused which damages. There are possible exemptions, protections, and defenses, such as whether the PFAS was released as part of an act of war, or to exempt a cleanup contractor from being liable for damages.

In January 2024, EPA released finalized PFAS measurement methods, added seven PFAS to the Toxics Release Inventory, and finalized a rule limiting companies’ ability to produce “inactive,” or infrequently used, PFAS. This was followed by EPA’s proposed February 2024 regulations that would add nine PFAS to a hazardous material list and cement the authority of EPA and states to mandate cleanup of the substances. These actions emphasized EPA’s commitment to addressing forever chemicals.

The EPA’s finalization of the National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) in April 2024 is perhaps one of the most significant actions taken by the agency on PFAS. Under the rule, maximum contaminant levels for drinking water will be established for six PFAS, including PFOA, PFOS, GenX, PFNA, PFHxS, and PFBS. Public water systems will be responsible for monitoring levels of the six PFAS and removing PFAS in excess of the maximum levels. Systems have until 2029 to implement programs that bring their water into compliance with these standards, at which point violations must be shared with the public and remediated. In September 2024, the White House also released a new research strategy for federal forever chemicals research, aiming to detail ways agencies can contribute to the PFAS research effort.

Selected Actions EPA Has Taken on PFAS in 2024 |

||

Regulation |

Status |

Significance |

|

Final CERCLA Hazardous Substances Designations for PFOA and PFOS |

Finalized |

Polluters who released PFOA and PFOS can now be liable for cleanup, with a focus on parties who contributed significantly. |

|

Finalized |

Drinking water facilities must ensure that the water does not exceed maximum contaminant levels for six PFAS. |

|

|

Updated interim guidance |

Strategies like underground injection, thermal treatment, and storage in permitted hazardous waste landfills are some of the recommended technologies for PFAS disposal. |

|

|

Released final methods January 2024 |

There are now three approved methods that can be used to measure PFAS in the air, wastewater, surface water, soil, biosolids, and landfill leachate. |

|

|

Requiring Toxics Release Inventory Reporting for Seven Additional PFAS |

Announced January 2024 |

Seven PFAS will be added to the Toxics Release Inventory, making it mandatory to report on their use above a certain threshold. |

|

Finalized January 2024 |

Companies must undergo a complete EPA review and risk determination before manufacturing 329 types of PFAS that have not been made in years. |

|

Source: Environmental Protection Agency

Federal Legislation

In the 118th Congress, dozens of bills were introduced on the topic of forever chemicals, with scopes ranging from PFAS study and education to regulation, exposure compensation, and liability protection. The only pieces of PFAS-related legislation enacted into law this Congress, as of August 2024, are the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024 (NDAA) (P.L. 118-31) and the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024 (P.L.118-63). The NDAA includes sections that limit the reporting requirements of the PFAS Task Force, require a budget justification for PFAS-related activities at DOD, incentivize the development of strategies for PFAS destruction, authorize DOD treatment of contaminated materials, and outline requirements for Government Accountability Office reporting on contamination at military sites. Meanwhile, the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) reauthorization would support a PFAS replacement program at airports.

While some proposed PFAS legislation focuses on limiting liability for PFAS cleanup, most bills aim to protect people from harm, and over half are bipartisan. The topics addressed range widely. As an example, the PFAS Alternatives Act (H.R.4769), with 92 bipartisan cosponsors, would encourage the development of firefighting gear without PFAS. Meanwhile, the Vet PFAS Act (H.R.4249/S.2294), with 40 bipartisan cosponsors between the House and Senate, would make veterans and their family members with health conditions caused by PFAS contamination at military bases eligible for certain Department of Veterans Affairs medical services. The PFAS Action Act (H.R.6805), with 27 cosponsors, including both Republicans and Democrats, would call on the EPA to designate PFOA and PFOS as hazardous under CERCLA. The Department of Defense PFAS Discharge Prevention Act (H.R.6095), with 14 bipartisan cosponsors, would require Department of Defense facilities to monitor PFAS discharge quarterly and implement best practices to reduce such discharges. Finally, the Relief for Farmers Hit with PFAS Act (S.747), with 11 cosponsors across three parties, would establish U.S. Department of Agriculture grants to help expand PFAS testing, research PFAS remediation in water and soil, and provide funding and assistance for farms with PFAS contamination. Other bipartisan bills would target public awareness, usage in cosmetics, disposal funding, remediation standards, government procurement, federal coordination efforts, discharge monitoring requirements, and service member compensation.

State and Local Laws and Regulation

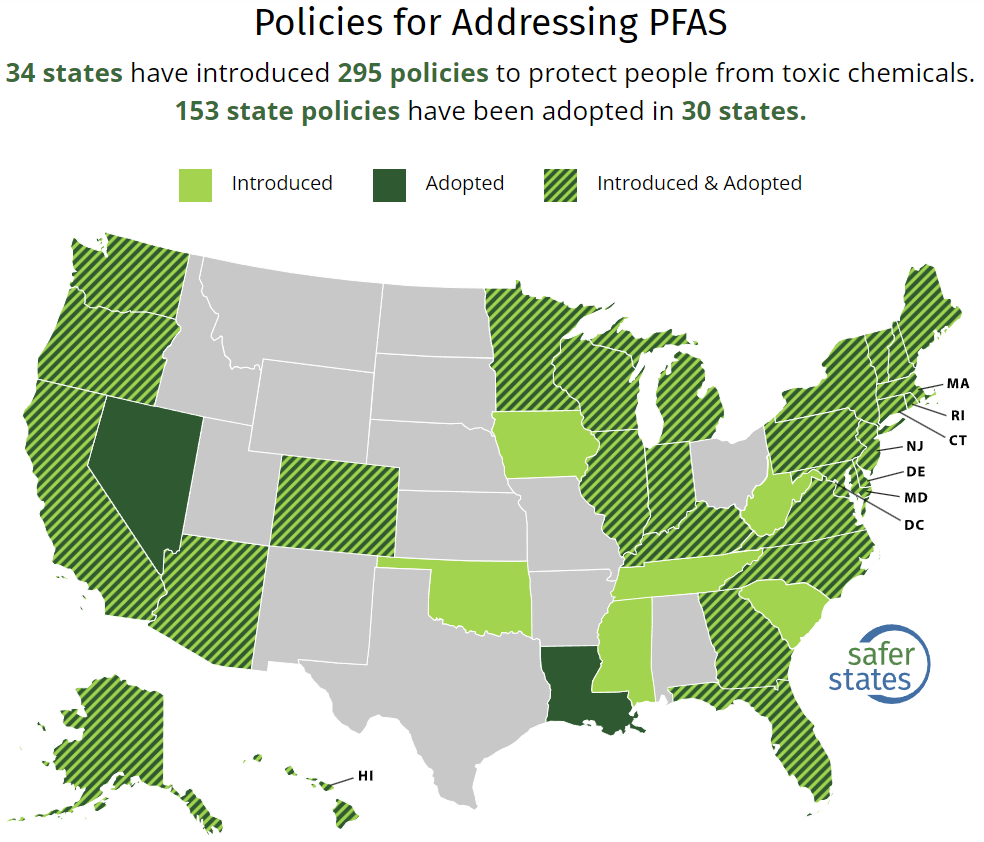

While Congress and EPA continue to advance federal PFAS policy, many states have also moved to address forever chemicals. Twenty-eight states have enacted policies to mitigate the proliferation and harms of PFAS, and six more have proposed similar policies. This includes policies on levels of PFAS in drinking water. Eleven states mandate specific drinking water limits for at least one PFAS chemical and another 12 states are adopting guidance or community notification programs on PFAS in drinking water.

|

Courtesy: Safer States |

|

The EPA’s proposed National Primary Drinking Water Regulation, described in the Federal Regulation section, would preempt states’ individual standards, setting maximum contaminant levels for six PFAS and mandating that water systems treat drinking water to these national standards. In order to comply with the rule, states will need to build and manage the equipment necessary to treat PFAS. While the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act includes assistance for water providers, these updates are still expected to cost hundreds of millions of dollars. |

In addition to policies on drinking water, states are also taking action on “upstream” PFAS concerns, particularly on regulations related to manufacturing processes. Fifteen states are imposing, or will soon impose, specific regulations on PFAS in certain products. Twelve states have chosen to phase out PFAS in food packaging, while 14 states are working to phase it out in firefighting foam. Some states are also moving to phase out PFAS in categories like apparel, personal care products, and children’s products. Maine, Minnesota, and Washington state stand out for committing to phase out PFAS in all products.

Lawsuits are another way states are addressing forever chemicals. Thirty state attorneys general are suing, or have sued, PFAS manufacturers for contamination (some of these lawsuits have already been settled). But it is not just manufacturers that are the targets of lawsuits. The states of New York, New Mexico, and Washington, as well as cities, businesses, and individuals have pursued lawsuits against the U.S. government for the harms of firefighting foam. However, the U.S. Department of Justice claimed immunity from 27 of these lawsuits in 2024, requesting that they be dismissed by a district court, citing the “discretionary function” exception of the Federal Tort Claims Act, which is meant to prevent courts from second-guessing federal government decisions. If this claim of immunity becomes precedent, states will need to look elsewhere for ways to fund PFAS remediation, mitigation, and compensation.

At the local level, municipalities consider themselves “passive receivers” of forever chemicals. They did not manufacture them, but still must deal with PFAS in their water supply and landfills. Meanwhile, local airports and fire departments were mandated to use PFAS firefighting foam, complicating questions about their responsibility. Cities are concerned about being held liable for PFAS contamination under CERCLA (see the “Federal Regulation” section). The additional costs and responsibilities associated with PFAS cleanup could prove challenging for cities, municipalities, and water districts. Cities including Dallas, Texas; Tacoma, Washington; and Las Cruces, New Mexico objected to class action contamination settlements reached with chemical companies 3M, Dupont de Nemours, and others, claiming that the settlement funds would not be nearly enough to cover their expenses. However, it is worth noting that an April 2024 policy memo published by the EPA indicated that the agency does not intend to pursue CERCLA actions or costs from entities like certain farms, public airports, local fire departments, storm sewer systems, municipal landfills, and community water systems where “equitable factors do not support seeking response actions or costs under CERCLA.”

Mitigation and Remediation

Regulation and legislation can help prevent PFAS from being manufactured in or imported into the United States. These pathways can also mandate the remediation of PFAS, highlighting the importance of finding strategies to treat and remove forever chemicals.

For drinking water, EPA has outlined strategies to treat PFAS, including activated carbon, ion exchange, and high pressure membranes. According to EPA, these treatments can be applied at the water treatment facility level as well as at the level of individual homes and building systems. Treatment at the water plant level will be crucial for meeting the 2024 National Primary Drinking Water Regulation standards (described in the “Federal Regulation” section).

Strategies to remediate PFAS in wastewater are also essential. PFAS can enter the wastewater stream via industrial processes and landfill leachate. Normally-treated wastewater can still contaminate groundwater, wildlife, and food because wastewater is generally not treated for PFAS.

The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) studied the 13 most promising current technologies for destroying certain PFAS in wastewater in Minnesota. The agency’s report highlighted the best available treatment technologies for different applications, after considering factors like scalability, destruction efficiency, public health, energy consumption, and maintenance costs. The final recommended treatments include combinations of granular activated carbon (GAC) sorption, single-use anion exchange (AIX), and reverse osmosis membrane separation to separate the PFAS from the water. In each case, the resulting solids containing the PFAS are incinerated at a high temperature.

Ultimately, the authors found that the highest ranked treatments, when adjusted for Minnesota’s specific environment, would cost the state at least $14 billion for liquid waste streams, and at least $105 million for water resource recovery facility biosolids.

Forever chemicals are also a concern in soil. PFAS can enter soil through groundwater, compost, irrigation, soil additives, air pollution, landfills, and pesticides. When PFAS-tainted “sewage sludge,” a biosolid byproduct of water treatment, is spread on cropland, the chemicals can spread to crops and the soil they grow in, as well as groundwater, livestock, and farmers themselves. As of November 2023, 23 states have regulated PFAS levels in soil, though these limits vary widely from state to state.

Soil washing, which uses liquids and mechanical processes to scrub soils, holds promise for soil remediation. Soil washing has demonstrated the ability to remove between 70% and 90% of PFAS, allowing the soil to be repurposed once contaminant levels are determined to be safe. Efforts are also underway to find ways to manage and remediate other sources of contamination, like waste milk, animal manure, and animal carcasses.

Author: Molly Brind’Amour

Editors: Daniel Bresette, Amaury Laporte

For the endnotes, please download the PDF version of this issue brief.

Advancing science-based climate solutions

Advancing science-based climate solutions